Linkfest:Nov 13,2013

Some stuff I am reading today morning:

New US Immigration Bill will decimate Indian IT companies (ET)

RCom’s opacity should irk investors (Mint)

CIDCO bats for hybrid model to levy fees for Navi Mumbai airport (BS)

Why western criticism of India’s Mars mission is blatant racism (Firstpost)

How to write your will (Subramoney)

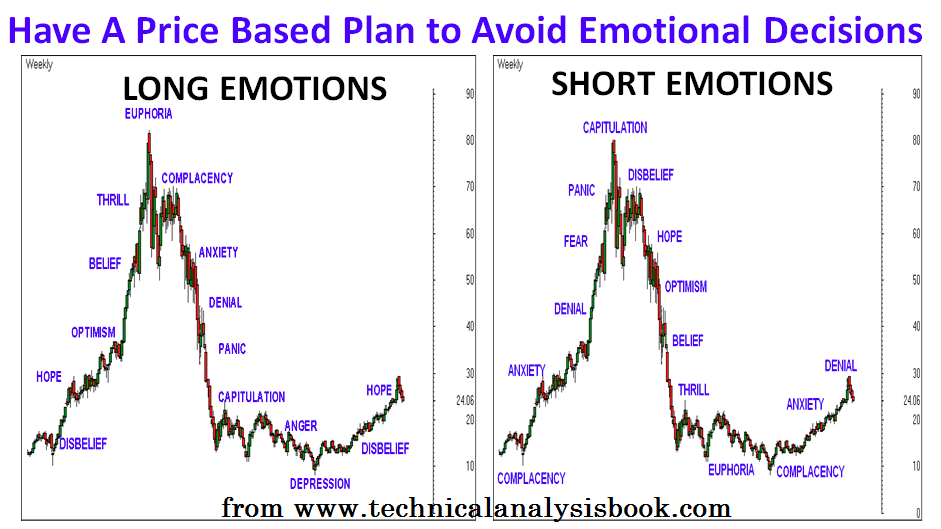

10 laws of stock market bubbles (Street)

Ray Dalio:You are not going to generate alpha (Marketwatch)

Financial innovation is depressing (Bloomberg)

List of LIC’s closed plans (BasuNivesh)

Everything you need to know about stock market crashes (TRB)

Chart:Emotions of Long & Short

An Iranian Shi’ite Muslim businessman now living abroad, who asked to remain anonymous because he still travels to Iran, said he attempted two years ago to sell a piece of land near Tehran that his family had long owned. Local authorities informed him that he needed a “no objection letter” from Setad.

The businessman said he visited Setad’s local office and was required to pay a bribe of several hundred dollars to the clerks to locate his file and expedite the process. He said he then was told he had to pay a fee, because Setad had “protected” his family’s land from squatters for decades. He would be assessed between 2 percent and 2.5 percent of the property’s value for every year.

Setad sent an appraiser to determine the property’s current worth. The appraisal came in at $90,000. The protection fee, he said, totaled $50,000.

The businessman said he balked, arguing there was no evidence Setad had done anything to protect the land. He said the Setad representatives wouldn’t budge on the amount but offered to facilitate the transaction by selling the land itself to recover its fee. He said he hired a lawyer who advised him to pay the fee, which he reluctantly did last year.-from Reuters

Me:So business is down?

He:Very down

Me:So how do you spend your time?

He:Go to office in the morning.First I have tea and then I read the newspaper

Me:Then?

He:Return home for lunch.After some rest, back to the office

Me:Then?

He:Now I read the newspaper first and then I have tea !!